Itching that won’t quit. No rash. No bug bites. Just relentless, deep, bone-deep itch - especially at night - that makes sleep impossible and daily life unbearable. For people with cholestatic liver disease, this isn’t just discomfort. It’s a relentless symptom that can be worse than the disease itself. This is cholestatic pruritus, and it affects up to 70% of those with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), 15% with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and nearly a third of pregnant women with intrahepatic cholestasis. And here’s the twist: antihistamines, the go-to for most itches, don’t work. Not because they’re weak, but because the cause isn’t histamine. It’s bile acids, opioids in the brain, and a newly discovered pathway involving lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and the enzyme autotaxin.

Why Bile Acid Resins Are Still the First Step

Cholestyramine, sold under the brand name Questran, has been the first-line treatment for decades. It’s not glamorous. It’s a gritty, chalky powder you mix with water or juice. But it works - for about half to two-thirds of patients. The mechanism is simple: cholestyramine is a bile acid resin. It binds to bile acids in your gut before they can be reabsorbed. Those bound acids then get flushed out in your stool instead of circling back to your liver and bloodstream. Less bile acid in the blood means less itching. The standard dose starts at 4 grams once a day. If it helps, your doctor will slowly increase it to 16 or even 24 grams daily, split into two or three doses. But there’s a catch. Cholestyramine doesn’t just bind bile acids. It binds everything - antibiotics, thyroid meds, birth control pills, even vitamins. That’s why you have to take it at least one hour before or four to six hours after any other medication. Miss that timing, and you risk making your other treatments useless. And then there’s the taste. A 2020 survey in Liver International found 78% of patients hated how it tasted. Another study of 342 patients showed 65% gave up on it within three months because of the texture and nausea. Still, for many, it’s the only thing that gives relief. One Reddit user wrote: “It’s awful, but when it works, it’s the only thing that cuts through the itch. I mix it with apple sauce and pretend it’s pudding.”When Cholestyramine Isn’t Enough: Rifampin and Naltrexone

If cholestyramine fails or becomes unbearable, the next step is rifampin. This is an antibiotic, but here, it’s not fighting infection. It’s tricking your liver. Rifampin turns on enzymes that help your body break down and eliminate the itch-causing substances faster. In PBC patients, it works in about 70-75% of cases. A 2019 review in the Journal of Hepatology showed most people feel better within two to four weeks. But it’s not clean. Rifampin turns your urine, sweat, and tears a bright orange. It’s startling at first, but harmless. The bigger risk is liver stress - about 15-20% of users see their liver enzymes rise. That’s why your doctor will monitor your blood work closely. It also interacts with over 50 other medications, including blood thinners, birth control, and some antidepressants. If you’re on multiple drugs, rifampin might not be safe. Then there’s naltrexone. This is the same drug used to treat opioid addiction. It blocks opioid receptors in the brain - and in cholestasis, those receptors seem to be involved in the itch signal. Dosed between 12.5 and 50 mg daily, it helps about 50-65% of patients. But the start is rough. About 30% of people feel like they’re going through opioid withdrawal in the first few days: nausea, anxiety, sweating, even insomnia. That’s why doctors start low - 6.25 mg - and creep up slowly. One patient in a 2022 focus group said: “The first three days felt like I was dying. I stopped. But if you can push through, the itch disappears.”The New Kid on the Block: Maralixibat and Beyond

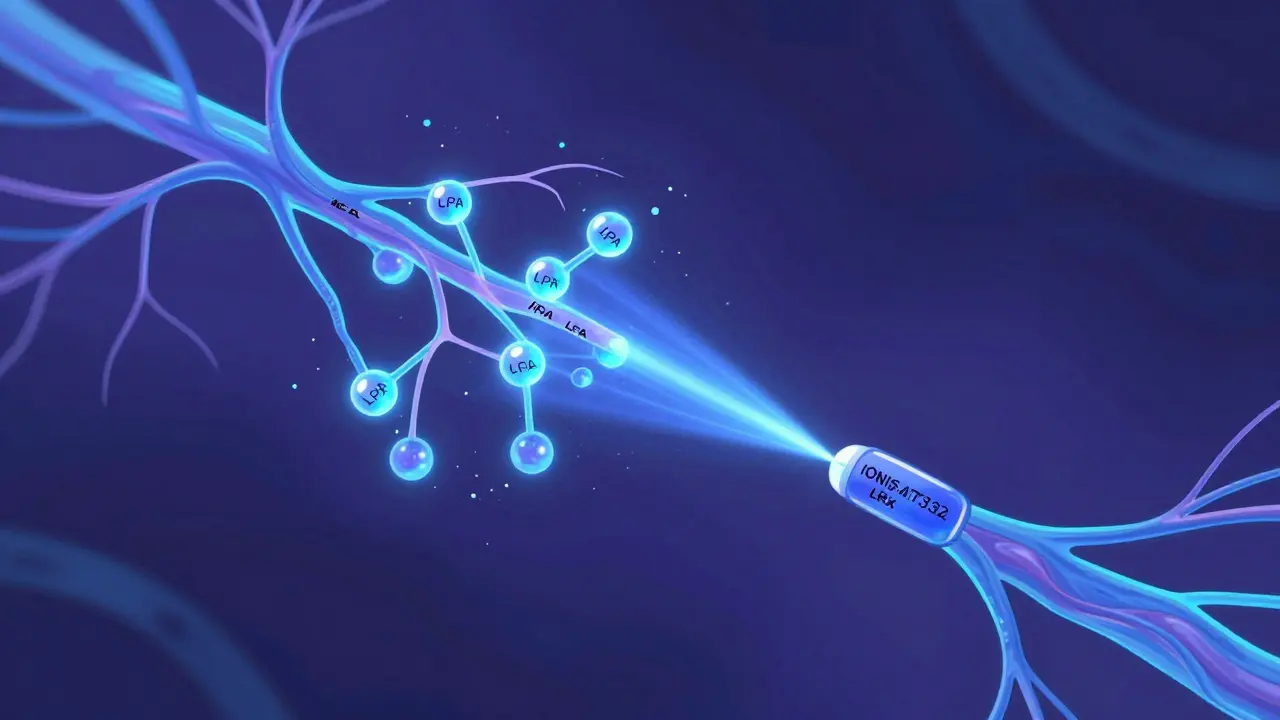

The real game-changer came in 2021 when the FDA approved maralixibat (brand name Mytesi) for children with Alagille syndrome. It’s not just for kids anymore. Studies show it works in adults with cholestatic pruritus too. Maralixibat blocks a protein in the gut called IBAT, which is responsible for pulling bile acids back into the body. Less reabsorption = less itch. In the MARCH trial (2022), maralixibat reduced itch by 47% on a standard scale - nearly matching cholestyramine’s 42%. But here’s the difference: only 12% of people quit maralixibat due to side effects, compared to 35% for cholestyramine. Patients report no gritty texture, no orange urine, no drug interactions. It’s a once-daily pill. A Cleveland Clinic survey in 2023 showed 82% of patients stayed on it after six months. But there’s a downside: cost. Maralixibat runs about $12,500 a month. Cholestyramine? About $65. That gap creates real access problems. Many insurance plans won’t cover it unless you’ve tried and failed everything else. And even then, approval can take months. Even newer drugs are coming. Volixibat, another IBAT inhibitor, showed 52% itch reduction in a 2023 trial. And then there’s the holy grail: drugs that target autotaxin, the enzyme that makes LPA. IONIS-AT332-LRx, an antisense oligonucleotide, cut serum autotaxin by 65% and reduced itch by 58% in a 2023 phase 2 trial. These aren’t just symptom blockers - they’re targeting the root cause.

What About Sertraline and Other Off-Label Options?

Sertraline (Zoloft), an SSRI antidepressant, is used off-label for cholestatic pruritus - especially in PBC patients. It’s not clear why it works, but it does. About 40-50% of patients report improvement. It’s especially helpful if the patient also has depression or anxiety, which are common in chronic itch. The dose is usually 75-100 mg daily. It’s not a first-line option, but it’s a useful tool when others fail. Other drugs like bezafibrate and fenofibrate (used for cholesterol) have shown modest benefit in small studies, but they’re not standard. And despite how often they’re prescribed, antihistamines like diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine have no proven benefit in cholestatic pruritus. A 2022 AASLD report found 68% of primary care doctors still prescribe them - but that’s based on habit, not science. The itch isn’t from histamine. It’s from bile acids and LPA. Antihistamines are like trying to put out a gas fire with water.When All Else Fails: Transplant and Lifestyle

For the 10-15% of patients who don’t respond to any medication, liver transplant is the only cure. And it works. About 95% of transplant recipients see their itching vanish completely. But it’s major surgery with lifelong risks. No one does it just for itching - only when liver function is failing or quality of life is destroyed. In the meantime, lifestyle tweaks help. Cool showers, unscented moisturizers, loose cotton clothing, and avoiding hot baths can reduce skin irritation. Some patients swear by capsaicin cream - it desensitizes nerve endings. Others find relief with acupuncture or mindfulness practices. None replace medication, but they make the daily grind more bearable.

The Big Picture: Where We’re Headed

We’re moving from treating symptoms to targeting the actual causes. The old approach - try cholestyramine, then rifampin, then naltrexone - still works. But it’s messy. Side effects pile up. Patients drop out. Costs soar. The future is precision: drugs that block autotaxin, IBAT inhibitors with better tolerability, maybe even gene therapies down the line. The AASLD and EASL guidelines now clearly lay out the stepwise path. But only 78% of academic centers follow it. In community clinics? Only 45%. Many doctors still don’t know the latest. Patients are left stuck on antihistamines, suffering in silence. The message is clear: if you have chronic, unexplained itching and a liver condition, don’t settle. Ask about bile acid resins. Ask about rifampin. Ask about maralixibat. And if your doctor prescribes an antihistamine first, ask why - because the evidence says it won’t help.Frequently Asked Questions

Is cholestyramine the only first-line treatment for cholestatic pruritus?

Cholestyramine is the most common first-line treatment, but it’s not the only option. Lifestyle changes like cool showers, moisturizers, and avoiding irritants are recommended alongside it. If cholestyramine isn’t tolerated or doesn’t work, guidelines support moving quickly to rifampin or other agents. Newer drugs like maralixibat are now being used earlier in some cases, especially when cost and access allow.

Why don’t antihistamines work for cholestatic itching?

Cholestatic pruritus isn’t caused by histamine, which is the chemical behind typical allergic itching. Instead, it’s driven by bile acids, endogenous opioids, and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) activating nerve pathways in the skin and spinal cord. Antihistamines block histamine receptors - but those receptors aren’t involved here. That’s why studies show no benefit, despite how often they’re prescribed.

How long does it take for rifampin to reduce itching?

Most patients notice improvement within two to four weeks of starting rifampin. Some feel better in as little as 10 days. The full effect usually takes four to six weeks. It’s important to stick with it at the prescribed dose - skipping doses or stopping early can prevent the full benefit. Urine discoloration is normal and harmless, but liver enzyme levels should be checked regularly.

Can maralixibat be used for all types of cholestatic liver disease?

Maralixibat is FDA-approved specifically for Alagille syndrome, but clinical trials show effectiveness in other cholestatic conditions like PBC and PSC. Many specialists now prescribe it off-label for adults with refractory pruritus. It’s not yet approved for every type of cholestasis, but research is ongoing. Insurance coverage often requires prior failure of first-line treatments like cholestyramine.

What are the biggest challenges with current treatments?

The biggest challenges are side effects, drug interactions, and cost. Cholestyramine is poorly tolerated due to taste and GI issues. Rifampin interacts with many medications and can stress the liver. Naltrexone causes withdrawal-like symptoms at start. Maralixibat is effective but costs over $12,000 a month. Many patients can’t access newer drugs due to insurance hurdles. Also, awareness among non-specialists remains low, leading to delayed or incorrect treatment.

Sophia Daniels

December 26, 2025 AT 10:41Let me tell you-this post is a goddamn masterpiece. Bile acids? Autotaxin? LPA? I didn’t know my itching had a PhD. Maralixibat sounds like a superhero drug that just skipped the comic book phase and went straight to the ER. And yet, $12,500 a month? That’s not medicine, that’s a luxury yacht with side effects. Meanwhile, I’m still mixing cholestyramine with peanut butter like it’s a survivalist smoothie. We’re living in the future, folks. And the future is expensive, gritty, and smells like regret.

Peter sullen

December 27, 2025 AT 13:15It is imperative to underscore the clinical significance of bile acid sequestrants in the management of cholestatic pruritus, particularly in the context of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). The mechanism of action of cholestyramine, as a non-absorbable anion-exchange resin, effectively interrupts the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids, thereby reducing their systemic concentration and subsequent neurosensory activation. Moreover, the pharmacokinetic interactions with concomitant medications necessitate precise temporal separation-ideally, a minimum of one hour pre- or four to six hours post-administration-to prevent subtherapeutic plasma concentrations of critical agents such as levothyroxine or oral contraceptives.

While newer agents like maralixibat demonstrate superior tolerability and adherence profiles in randomized controlled trials (e.g., MARCH, 2022), their cost-effectiveness remains a substantial barrier to equitable access, particularly within resource-constrained healthcare systems. The pharmacoeconomic burden of IBAT inhibitors must be contextualized against the long-term morbidity associated with uncontrolled pruritus, including sleep deprivation, depression, and diminished quality of life.

Furthermore, the emerging role of autotaxin inhibition as a disease-modifying strategy represents a paradigm shift from symptomatic palliation to targeted pathophysiological intervention. The phase II data for IONIS-AT332-LRx, demonstrating a 65% reduction in serum autotaxin and a concomitant 58% reduction in pruritus severity, warrants accelerated clinical development and regulatory prioritization.

Brittany Fuhs

December 29, 2025 AT 08:17So let me get this straight-we’ve got a $12,000 pill that works better than a chalky powder that tastes like wet cardboard, and half the country still can’t get it because some insurance adjuster thinks ‘it’s not first-line’? Meanwhile, doctors keep prescribing Benadryl like it’s 1998 and we’re all allergic to pollen. This isn’t medicine. This is capitalism with a stethoscope. And don’t even get me started on how we let Big Pharma turn liver disease into a profit margin.

Steven Destiny

December 30, 2025 AT 08:55STOP prescribing antihistamines. Just stop. It’s not just useless-it’s insulting. You’re telling someone who hasn’t slept in weeks that their bone-deep, soul-crushing itch is just ‘allergies’? That’s like giving a drowning person a snorkel and calling it a rescue. Maralixibat isn’t ‘new’-it’s the future. And if your doctor doesn’t know about it, find a new doctor. Your liver doesn’t care about your insurance plan. It just wants to stop screaming.

Fabio Raphael

December 31, 2025 AT 06:05I’ve been living with PBC for 11 years. Cholestyramine broke me. Rifampin turned me into a walking traffic cone. Naltrexone made me feel like I was dying for three days-then it saved my life. I didn’t believe in maralixibat until I tried it. Now I take it like a vitamin. I don’t care how much it costs. I care that I can hug my daughter without wanting to claw my skin off. If you’re reading this and you’re still on antihistamines? Please. Ask your doctor about IBAT inhibitors. You deserve to sleep.

Nikki Brown

January 2, 2026 AT 00:25Wow. Just... wow. I can't believe people still think antihistamines work for this. 😒 I mean, really? You're treating a nuclear reactor with a squirt gun? 🤦♀️ And don't even get me started on the fact that maralixibat costs more than my rent. But hey, at least the orange pee from rifampin is kinda cool. Like a glow stick for your insides. 😅

Becky Baker

January 3, 2026 AT 06:09Cholestyramine tastes like sandpaper dipped in regret. I mix it with chocolate syrup and lie to myself that it’s a milkshake. It’s the only thing that works. Rifampin? My urine looked like a highlighter exploded. Naltrexone? Felt like I was detoxing from heroin while sober. But maralixibat? That’s the one. No mess, no orange tears, just peace. Too bad it’s a luxury item. Guess I’m just lucky I got insurance. Not everyone is.

Erwin Asilom

January 4, 2026 AT 08:29For those struggling with this: you’re not alone. The itch is real. The exhaustion is real. The frustration with doctors who still reach for Benadryl? Also real. Don’t give up. Push for the next step. Ask for rifampin. Ask for maralixibat. If your provider says no, ask why-and then ask again. Your quality of life matters more than their inertia. You’re not asking for a miracle. You’re asking for science. And science has answers.

sakshi nagpal

January 5, 2026 AT 15:14As someone from India, I find it heartbreaking that such a life-changing drug is out of reach for so many. In my country, cholestyramine is the only option for most, and even that is hard to get consistently. The science here is brilliant-but medicine should not be a privilege. I hope global health initiatives take notice. No one should suffer in silence because of cost. We need equity, not just innovation.

roger dalomba

January 7, 2026 AT 12:15So… we have a drug that works, but only if you’re rich? Cool. Cool cool cool. Meanwhile, my doctor still thinks I’m ‘just stressed.’ 🙃

Amy Lesleighter (Wales)

January 8, 2026 AT 11:29It’s not about the pill. It’s about the sleep. It’s about holding your kid without wanting to scream. Maralixibat isn’t magic-it’s just the first thing that didn’t make me want to quit. Keep pushing. You’re worth more than an antihistamine.