Opioid Hyperalgesia Diagnostic Tool

Assess Patient Symptoms

This tool helps clinicians differentiate between opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and tolerance based on key clinical patterns.

When a patient on long-term opioids says their pain is getting worse, most doctors assume one thing: they need a higher dose. But what if the problem isn’t that the medicine isn’t working - but that the medicine itself is making the pain worse? That’s opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), and it’s being missed far too often.

What Exactly Is Opioid Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is a paradox. You give someone opioids to reduce pain, and over time, their body becomes more sensitive to it. They don’t just feel their original pain more - they start feeling pain where there wasn’t any before. A light touch on the skin hurts. A breeze feels like sandpaper. The pain spreads beyond the original injury site. It’s not just more pain. It’s different pain.

This isn’t theoretical. Lab studies have shown it clearly in animals. In humans, it’s harder to prove because pain is subjective, but clinical patterns are consistent. Patients on high-dose opioids for years - especially for non-cancer chronic pain - often report worsening pain despite dose increases. That’s a red flag.

The mechanism? It involves the nervous system rewiring itself. NMDA receptors in the spinal cord get overactivated. Glial cells, which normally support neurons, start releasing inflammatory signals. Dynorphin, a natural pain modulator, gets thrown out of balance. The result? The body’s pain alarm system goes haywire.

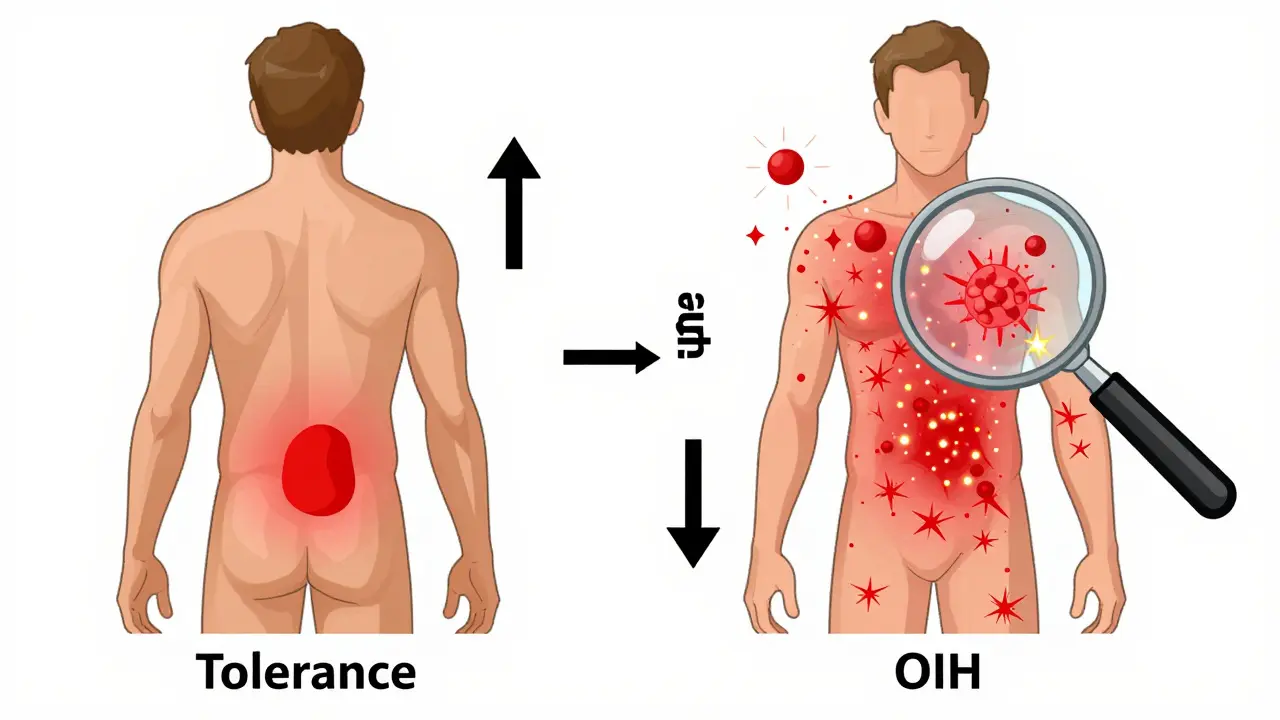

How Is It Different from Tolerance?

Tolerance and hyperalgesia get mixed up all the time. But they’re not the same.

Tolerance means you need more opioid to get the same pain relief. It happens to all opioid effects - pain relief, drowsiness, even breathing suppression. If you increase the dose, the pain usually gets better again. The pain pattern stays the same. It’s predictable.

OIH is the opposite. You give more opioid, and the pain gets worse. The pain spreads. It changes character. It becomes more widespread, more sharp, more sensitive to touch. You can’t fix it by increasing the dose - you make it worse.

Think of it this way: Tolerance is like turning down the volume on your stereo. You turn the knob up to hear it again. OIH is like the speakers are frying. Turning up the volume doesn’t help - it just makes the static louder.

Red Flags That Point to OIH

Here are the clinical clues that should make you pause before reaching for a higher opioid prescription:

- Pain worsens with dose increases. If the patient says, “I took more oxycodone and now my back hurts more than ever,” that’s not tolerance - that’s OIH.

- Pain spreads beyond the original area. Original pain was in the lower back. Now it’s in the hips, thighs, even the feet. That’s a sign the nervous system is sensitizing, not the disease progressing.

- Allodynia develops. Light pressure, clothing, or even a breeze causes pain. This is a hallmark of central sensitization - a key feature of OIH.

- Pain changes quality. It shifts from dull and aching to sharp, burning, or electric. That’s not typical disease progression - it’s neuroplastic change.

- No improvement after dose escalation. Tolerance responds to higher doses. OIH doesn’t. If you’ve doubled the dose and the patient is worse, suspect OIH.

- Pain worsens during stable dosing. If the dose hasn’t changed but the pain is creeping up, it’s likely not withdrawal - it’s hyperalgesia building quietly.

One patient I saw had been on 120 mg of oxycodone daily for six years after a herniated disc. Her pain had spread from her lower back to both legs, and even her hands hurt when she brushed her hair. She was told she was “tolerant.” But when we reduced her dose by 25% over three weeks, her pain dropped by 40%. That’s not tolerance. That’s OIH.

How to Diagnose It

There’s no blood test. No MRI that shows it. Diagnosis is clinical - based on pattern recognition.

Start with a detailed pain map. Have the patient draw where they hurt on a body diagram. Do this every visit. If the area keeps expanding, that’s a strong indicator of OIH. Compare it to their baseline drawing.

Use simple sensory tests. Ask them to rate pain from light touch with a cotton swab. If they say it’s painful, that’s allodynia. Test pinprick sensitivity - if it’s exaggerated, that’s hyperalgesia.

Track the dose-pain relationship. Keep a log: dose on Monday, pain score on a scale of 1-10. If higher doses consistently correlate with higher pain scores, OIH is likely.

And rule out other causes. Is there new nerve damage? A new injury? Infection? If not, and the pattern fits, treat it as OIH until proven otherwise.

What to Do When You Suspect OIH

Don’t keep increasing the opioid. That’s the worst thing you can do.

First, reduce the dose slowly - 10-25% every 1-2 weeks. Many patients improve even with modest reductions. Don’t fear withdrawal. OIH pain isn’t withdrawal. Withdrawal causes anxiety, sweating, diarrhea. OIH pain is localized, sensory, and worsens with dose.

Consider switching opioids. Some opioids - like methadone or buprenorphine - have NMDA-blocking effects, which may help reverse sensitization. Switching from morphine to methadone has helped many patients in clinical practice.

Add non-opioid medications. Low-dose naltrexone (LDN), ketamine patches, gabapentin, or even antidepressants like duloxetine can help calm the overactive nervous system. These aren’t painkillers - they’re nerve stabilizers.

Combine with non-drug therapies. Physical therapy that focuses on graded exposure to movement, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) help retrain the brain’s pain response. These aren’t optional extras - they’re essential.

Why This Matters Now

In 2021, New Zealand’s Medsafe agency explicitly warned that opioids are not recommended for chronic non-cancer pain because of risks like OIH. The FDA and EMA have issued similar warnings. Prescriptions are falling - in New Zealand, opioid use dropped 17% between 2018 and 2021.

Why? Because doctors are starting to see the cost. Patients with OIH often end up in emergency rooms, on higher doses, with more side effects, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates. They’re caught in a cycle no one taught them to recognize.

The real tragedy? Many patients are told they’re “addicts” or that their pain is “all in their head.” But OIH is real. It’s biological. It’s measurable. And it’s fixable - if you know what you’re looking for.

The Bottom Line

If your patient’s pain is getting worse on higher opioid doses - especially if it’s spreading or becoming more sensitive - don’t reach for the prescription pad. Reach for the pain map. Ask about touch sensitivity. Review the dose-pain log. Consider reduction.

Opioid tolerance is common. Opioid hyperalgesia is underdiagnosed. But it’s not rare. And it’s not untreatable. The first step is recognizing it for what it is: a side effect of the medicine, not a failure of the patient.

Stop treating pain with more opioids when the pain is getting worse. Start treating the nervous system - not just the symptom.

Can opioid hyperalgesia happen with low doses?

Yes. While it’s more common with high doses and long-term use, there are documented cases where patients on low to moderate doses developed hyperalgesia after several months. It’s not strictly dose-dependent - individual biology, genetics, and pain type matter. Someone on 30 mg of oxycodone daily for eight months can still develop OIH.

Is OIH the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a physiological change in pain processing. A patient can have OIH without being addicted - and vice versa. Confusing the two leads to stigma and poor care. OIH is a side effect. Addiction is a behavioral disorder.

How long does it take for OIH to develop?

There’s no fixed timeline. Some patients develop it after 3-6 months of regular use. Others take years. It depends on the individual, the opioid type, the dose, and genetic factors. People with pre-existing nerve sensitization - like those with fibromyalgia or migraines - may be more vulnerable.

Can OIH be reversed?

Yes, often. Many patients see significant improvement after tapering opioids, switching to a different opioid like methadone or buprenorphine, or adding NMDA antagonists. Recovery can take weeks to months. The nervous system can reset - but only if the trigger (high-dose opioids) is removed.

Should I stop opioids completely if I suspect OIH?

Not always. A slow, controlled taper - often 10-25% per month - is safer and more effective than abrupt stopping. Complete cessation isn’t necessary for everyone. The goal is to reduce the dose enough to reverse sensitization while maintaining some pain control. Many patients end up on much lower doses, or switch to non-opioid therapies entirely.

Are there tests to confirm OIH?

No single test confirms it. But quantitative sensory testing (QST) - measuring pain response to heat, cold, pressure, and touch - can support the diagnosis. Pain mapping and dose-pain logs are more practical in routine care. The diagnosis is clinical: if the pattern fits and other causes are ruled out, treat it as OIH.

Susie Deer

January 14, 2026 AT 16:44Opioids are just another government tool to keep us docile and addicted to painkillers so we don’t question the system

TooAfraid ToSay

January 16, 2026 AT 15:30Wait so you’re saying the medicine that’s supposed to help is actually the problem? That’s wild. I thought this was just a myth made up by people who hate opioids

Dylan Livingston

January 16, 2026 AT 16:21Oh wow. Another beautifully articulated piece of medical literature that somehow manages to sound like a TED Talk written by a grad student who just discovered NMDA receptors. Of course, the real tragedy isn't OIH-it's that we still let pharmaceutical reps dictate pain management like it's 1998. The fact that this isn't taught in med school during orientation is a national disgrace. And don't get me started on how the FDA's warnings are just performative gestures while Big Pharma keeps funding every damn pain conference. We're not treating patients-we're managing liability.

Andrew Freeman

January 16, 2026 AT 22:03so u mean like if u take more oxy and ur pain gets worse its not ur body just needing more its the drugs makin u more sensitive?? that actually makes sense now that i think about it

says haze

January 17, 2026 AT 03:41What’s fascinating is how this phenomenon mirrors the broader epistemological crisis in modern medicine-where symptom suppression is mistaken for healing. OIH isn’t just a pharmacological artifact; it’s a metaphor for our collective refusal to engage with the root causes of suffering. We pharmaceuticalize pain because confronting trauma, socioeconomic decay, and existential isolation is too uncomfortable. The body doesn’t lie. It screams. And we keep turning up the volume.

Alvin Bregman

January 17, 2026 AT 16:22i’ve seen this firsthand. my cousin was on 80mg of oxycodone for years after a car wreck. pain kept spreading. then they cut the dose down slowly and after a few months he was actually feeling better. not cured but better. like he could sleep without crying. nobody told him this could happen

Sarah -Jane Vincent

January 18, 2026 AT 07:41Of course this is real. The pharmaceutical industry knew about this for decades. They buried the studies. You think they care if you’re in agony? They just want you to keep buying. This isn’t medicine-it’s a racket. And now they’re pushing fentanyl patches like candy. Wake up people.

Jason Yan

January 18, 2026 AT 19:12This is one of the most important things I’ve read all year. I’ve been treating chronic pain for 15 years and I used to think dose increases were the answer. I was wrong. Learning about OIH changed how I talk to patients. It’s not about giving more drugs-it’s about listening to what their body is telling them. Sometimes the medicine is the problem. And that’s okay. We can fix it.

shiv singh

January 19, 2026 AT 20:56So you’re telling me the doctors are the problem? I’ve been on opioids for 10 years and I’m not weak. I’m not addicted. I’m just in pain. Now you want me to stop? What am I supposed to do? Just suffer? You think this is easy? You have no idea

Sarah Triphahn

January 20, 2026 AT 12:06Wow. So the real villain here is not the patient, not the addiction, but the damn pill. That’s rich. Meanwhile, the same people who wrote this are probably prescribing gabapentin like it’s water and calling it "nerve stabilization." Meanwhile, the patient is still crying in the ER. This is just another way to gaslight people into thinking their pain isn’t real unless it fits your checklist.

Vicky Zhang

January 21, 2026 AT 18:17I’ve been there. My mom was on high-dose opioids for fibromyalgia. She got worse. We thought it was her condition getting worse. Turns out it was the meds. When we tapered her slowly, she started sleeping through the night for the first time in 7 years. She cried. Not from pain-from relief. This isn’t just science. It’s human. Please share this with your doctor.

Allison Deming

January 23, 2026 AT 08:59While the clinical observations presented are indeed compelling, one must consider the broader context of regulatory oversight, institutional inertia, and the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria for opioid-induced hyperalgesia. The absence of a validated biomarker renders this entity largely inferential, and thus, its recognition remains susceptible to confirmation bias. Until large-scale, prospective, double-blind trials confirm the reversibility of this phenomenon independent of placebo effects, caution in clinical application is warranted.

Henry Sy

January 24, 2026 AT 10:10They call it hyperalgesia but it’s really just your body screaming "I’m not a drug vending machine". I was on 150mg a day. Felt like my skin was on fire. Cut it by 30%. Now I can wear a t-shirt without wanting to scream. It’s not magic. It’s biology. And yeah, it’s terrifying to go off them-but worse is staying on and turning into a human pin cushion.

Anna Hunger

January 25, 2026 AT 20:59Thank you for this meticulously documented and clinically sound exposition. The integration of quantitative sensory testing with longitudinal pain mapping represents a paradigm shift in chronic pain management. I have shared this with my department for inclusion in our continuing education modules. The ethical imperative to recognize and mitigate opioid-induced hyperalgesia cannot be overstated.

Robert Way

January 26, 2026 AT 23:22wait so if i stop the oxy my pain gets better? but what if i need it? i mean like what if i just cant function without it? this sounds like a trap