When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do we know it really does? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most common and trusted method regulators use to prove that a generic drug is the same as the original. Yet calling it the "gold standard" is misleading. It’s not perfect. It’s not always enough. And for some drugs, it’s barely even the best option.

What Pharmacokinetic Studies Actually Measure

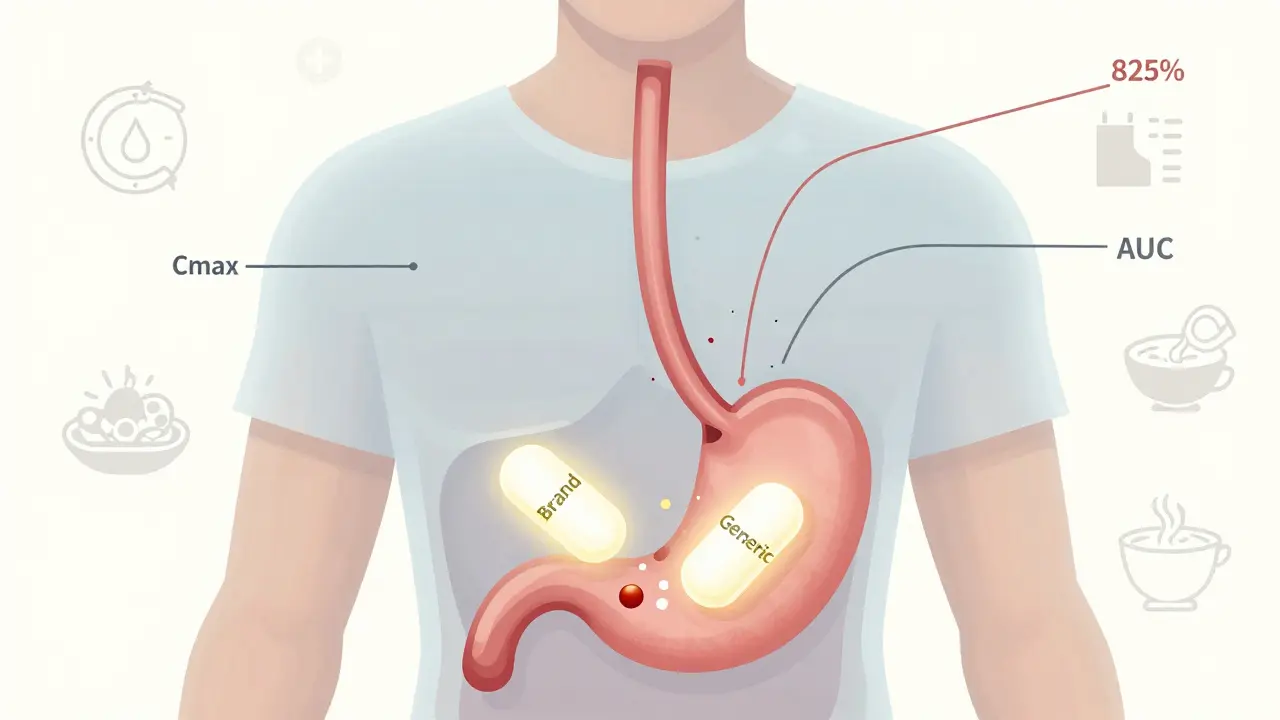

Pharmacokinetic studies track how your body handles a drug after you take it. They measure two key things: how fast the drug gets into your bloodstream (Cmax), and how much of it gets there over time (AUC). These numbers tell regulators whether the generic version releases the same amount of active ingredient at the same speed as the brand-name drug.The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for both Cmax and AUC falls between 80% and 125% when comparing the generic to the original. That means if the brand-name drug delivers 100 units of medicine into your blood, the generic must deliver between 80 and 125 units. It’s not about being identical-it’s about being close enough that your body won’t notice the difference.

These studies are done in healthy volunteers, usually 24 to 36 people, in a crossover design. That means each person takes both the generic and the brand-name version at different times, with a clean break in between. They’re tested under two conditions: fasting and after eating. Why? Because some drugs, like certain antibiotics or cholesterol meds, absorb differently when food is in the stomach. If the drug’s absorption changes with food, regulators need to know that the generic behaves the same way.

Why It’s Not Actually the "Gold Standard"

The FDA doesn’t call pharmacokinetic studies the "gold standard." They call them a "fundamental principle." There’s a big difference. A gold standard implies perfection-something you can trust absolutely. But pharmacokinetic studies are a proxy. They measure what’s easy to measure: blood levels. They don’t directly measure whether you feel better, whether your blood pressure drops, or whether your seizures stop.For most drugs, this works fine. The FDA’s own data shows less than a 2% failure rate for immediate-release oral drugs after approval. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, phenytoin, or digoxin-small differences can be dangerous. For these, the FDA tightened the range to 90-111%. Even then, there are cases where two generics with identical blood levels still caused different clinical outcomes.

One study in PLOS ONE found that two generics made by different manufacturers, both matching the innovator drug’s in vitro profile and pharmacokinetic data, still had significantly different effects on patients’ blood clotting times. That’s not a flaw in the study design. It’s a flaw in assuming that blood concentration = clinical effect.

Where Pharmacokinetic Studies Fall Short

Not all drugs travel through your bloodstream the same way. Topical creams, inhalers, eye drops, and injectables don’t rely on systemic absorption. For these, measuring blood levels tells you almost nothing.Take a steroid cream for eczema. You don’t want to know how much gets into the blood-you want to know how much gets into the skin and how well it reduces inflammation. That’s where dermatopharmacokinetic methods and in vitro permeation testing come in. One 2014 study showed that testing drug penetration through human skin in the lab was more accurate and less variable than running clinical trials with hundreds of patients.

Same goes for inhaled asthma medications. The amount of drug in your blood doesn’t tell you if it’s reaching your lungs properly. The particle size, the spray mechanism, the way you inhale-all of that matters. Pharmacokinetic studies can’t capture that. Regulatory agencies are starting to require lung deposition tests or clinical endpoint trials for these products, even though they’re expensive and slow.

The Cost and Complexity Behind the Numbers

Running a single bioequivalence study isn’t cheap. It costs between $300,000 and $1 million. It takes 12 to 18 months from formulation to final report. For a company making dozens of generics, that adds up fast.And it’s not just about money. Formulation changes that seem tiny-switching one excipient, changing the granulation process-can wreck bioavailability. Two pills might have the same active ingredient, the same dose, the same coating… and still behave completely differently in the body. That’s why the FDA now has 1,857 product-specific guidances for generic drugs. There’s no one-size-fits-all rule.

Some companies try to avoid full bioequivalence studies by using the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). If a drug is highly soluble and highly permeable (BCS Class I), and the formulation is simple, regulators may waive the human study. But only about 15% of drugs qualify. For the rest, you’re stuck with the blood tests.

Global Differences and Regulatory Chaos

The U.S. and Europe don’t always agree. The FDA uses product-specific guidelines-meaning each drug gets its own rules. The EMA tends to apply the same standards across the board. That creates headaches for manufacturers trying to sell the same generic in both markets.And then there’s the rest of the world. The WHO says 50 countries follow international bioequivalence guidelines. But enforcement? That’s another story. In some places, generic drugs enter the market with minimal testing. The result? Patients get pills that look right but don’t work right.

Harmonization efforts like ICH M13A are helping. Thirty-five countries now follow the same basic framework for immediate-release oral drugs. But for complex products-modified-release tablets, suspensions, transdermal patches-there’s still no global consensus.

The Future: PBPK Models and Beyond

The field is changing. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is now accepted by the FDA to support bioequivalence waivers for certain drugs. Instead of testing on people, scientists build computer models that simulate how a drug moves through the body based on its chemical properties, stomach pH, liver enzymes, and more.For BCS Class I drugs, this is already replacing human studies. It’s faster, cheaper, and more predictable. The FDA approved its first PBPK-based waiver in 2020. Today, it’s being used for antibiotics, antivirals, and other well-understood compounds.

But it’s not magic. PBPK models need high-quality data to work. They can’t predict how a new excipient will behave unless it’s been tested before. For complex formulations, they’re still a tool-not a replacement.

What’s clear is that the old model-rely on blood levels, approve the generic-is crumbling. The future is smarter, more targeted, and more complex. For some drugs, pharmacokinetic studies will stay central. For others, they’ll be just one piece of a much bigger puzzle.

What This Means for You

If you’re taking a generic version of a common drug-like lisinopril, metformin, or atorvastatin-you can be confident it works. The system works well for these.But if you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug-like levothyroxine, warfarin, or cyclosporine-stick with the same brand or generic unless your doctor says otherwise. Switching between generics can cause problems, even if they’re "approved."

And if you’re prescribed a topical cream, inhaler, or eye drop, know that the blood test you hear about in the news doesn’t apply. Those drugs are evaluated differently, and not always as rigorously.

Generic drugs save billions. They’re essential. But they’re not all created equal. Pharmacokinetic studies are the backbone of the system-but they’re not the whole body.

Are pharmacokinetic studies always required for generic drugs?

No. For some drugs, especially those classified as BCS Class I (highly soluble and highly permeable), regulators like the FDA may waive human bioequivalence studies if the formulation is simple and the drug has a well-understood absorption profile. In vitro dissolution testing and computational models like PBPK can be used instead. But this applies to only about 15% of generic drugs.

Why do some generic drugs cause different side effects than the brand name?

Even if two drugs have identical active ingredients and pass pharmacokinetic tests, differences in inactive ingredients (excipients) can affect how quickly the drug dissolves or how it’s absorbed. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like levothyroxine or warfarin-these small differences can lead to noticeable changes in effectiveness or side effects. That’s why switching generics on these drugs isn’t always safe.

Do all countries use the same bioequivalence standards?

No. While many countries follow WHO or ICH guidelines, enforcement and specific requirements vary. The FDA uses product-specific guidances, while the EMA tends to apply broader rules. Some emerging markets have weaker oversight, leading to generics entering the market with insufficient testing. This is why the same generic drug might be approved in the U.S. but not in Europe-or vice versa.

Can in vitro tests replace human pharmacokinetic studies?

For some drugs, yes. For immediate-release oral drugs with simple formulations, well-designed dissolution tests can predict bioequivalence reliably. For topical products, in vitro permeation testing through human skin has proven more accurate than clinical trials. The FDA and EMA now accept these methods under specific conditions, especially when supported by strong scientific data. But they’re not universal replacements.

What’s the biggest limitation of pharmacokinetic studies?

They measure blood levels, not clinical outcomes. Two drugs can have identical Cmax and AUC values but still produce different effects in patients-especially for drugs that act locally (like inhalers or creams) or have complex pharmacodynamics (like anticoagulants). Pharmacokinetics tells you the drug got into the blood. It doesn’t tell you whether it did what it was supposed to do.

Conor Flannelly

January 28, 2026 AT 08:00Pharmacokinetics is the skeleton of generic approval, but it’s not the soul. I’ve seen patients on warfarin switch generics and end up in the ER not because the blood levels were off, but because one had a different filler that altered dissolution speed. We treat drugs like interchangeable parts, but bodies aren’t assembly lines. 🤔

Conor Murphy

January 29, 2026 AT 16:22Big respect for calling out the ‘gold standard’ myth. It’s like saying a thermometer measures health. Blood levels tell us part of the story, but not the whole damn novel. Especially for inhalers-how the hell do you know if the drug even got to the lungs if you’re only checking plasma? 🫁

Desaundrea Morton-Pusey

January 31, 2026 AT 08:32Why are we even talking about this? If it’s FDA-approved, it’s fine. Stop overcomplicating things. People are just scared of saving money. 🇺🇸

John O'Brien

February 1, 2026 AT 09:56Bro the whole system is rigged. I work in pharma and saw a generic get approved because they tweaked the coating just enough to pass the 80-125% range but still made patients nauseous. No one cares until someone gets hurt. And then it’s ‘oops, we didn’t test that’.

Kegan Powell

February 2, 2026 AT 08:23Love this breakdown honestly. PBPK models are the future but they’re still babies compared to real human data. I’ve seen models predict perfect bioequivalence then the real-world data shows a 20% drop in absorption because someone’s gut pH was off from antibiotics. We need both. Not either or. 🙌

April Williams

February 3, 2026 AT 04:19So you’re telling me I could be on a generic that’s technically ‘approved’ but actually making me feel worse? And the FDA just shrugs? This is why I don’t trust any of it. My thyroid meds switched and I gained 20 pounds in 3 months. No one even apologized.

astrid cook

February 5, 2026 AT 00:01People don’t realize how dangerous this is. You think it’s just ‘a pill’ but for someone on digoxin, a 5% difference in absorption can be fatal. And regulators let this slide because it’s cheaper. That’s not science. That’s capitalism wearing a lab coat.

Andrew Clausen

February 6, 2026 AT 03:37You state that pharmacokinetic studies are a 'proxy'-this is inaccurate terminology. A proxy implies substitution, but PK data is the primary metric used for bioequivalence determination under current regulatory frameworks. The term 'fundamental principle' is correct; 'proxy' is misleading and semantically incorrect. Also, 'gold standard' is not used by the FDA in this context, but your critique of the system is valid regardless.

Kirstin Santiago

February 7, 2026 AT 09:43My mom’s on levothyroxine and we switched generics twice because of insurance. She got dizzy, her heart raced, her TSH spiked. We went back to the brand. No one warned us. If you’re on a narrow index drug, don’t switch unless you’re monitored. And if your doctor says ‘it’s the same,’ ask them if they’ve ever seen a patient crash after a switch. They’ll hesitate. That’s your answer.