When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle with a different name than what your doctor wrote, you might wonder: Is this really the same thing? It’s not just a label change. It’s a legal, scientific, and clinical decision made in seconds - and it’s backed by decades of regulation, data, and strict standards. Pharmacists don’t guess. They don’t rely on memory. They use a single, federally recognized tool to verify that a generic drug is safe to swap for the brand-name version: the FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, better known as the Orange Book.

What Exactly Is Therapeutic Equivalence?

Therapeutic equivalence isn’t about looking alike or costing less. It’s about function. A generic drug must deliver the same active ingredient, in the same amount, at the same speed, and in the same way as the brand-name drug. That’s three layers:- Pharmaceutical equivalence: Same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection), and route of administration.

- Bioequivalence: The generic must absorb into your bloodstream at nearly the same rate and amount as the brand. The FDA requires the 90% confidence interval for two key measurements - Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure) - to fall between 80% and 125% of the brand. For high-risk drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, that window tightens to 90-111%.

- Therapeutic equivalence: The final verdict. If the first two are met, the FDA says: ‘You can swap these without risk.’

That’s not theory. It’s data. A 2020 FDA meta-analysis of over 1.2 million patient records found the rate of adverse events after switching from brand to generic was 0.78% - compared to 0.81% for brand-only use. The difference? Statistically meaningless.

The Orange Book: The Only Legal Reference

The Orange Book is the only document that gives pharmacists legal permission to substitute. Every state in the U.S. - except Massachusetts - requires pharmacists to use it. Texas law, for example, explicitly states: ‘Pharmacists shall use the Orange Book as the basis for determining generic equivalency.’The Orange Book uses a two-letter code for every drug:

- A = Therapeutically equivalent. Safe to substitute.

- B = Not equivalent. Don’t swap.

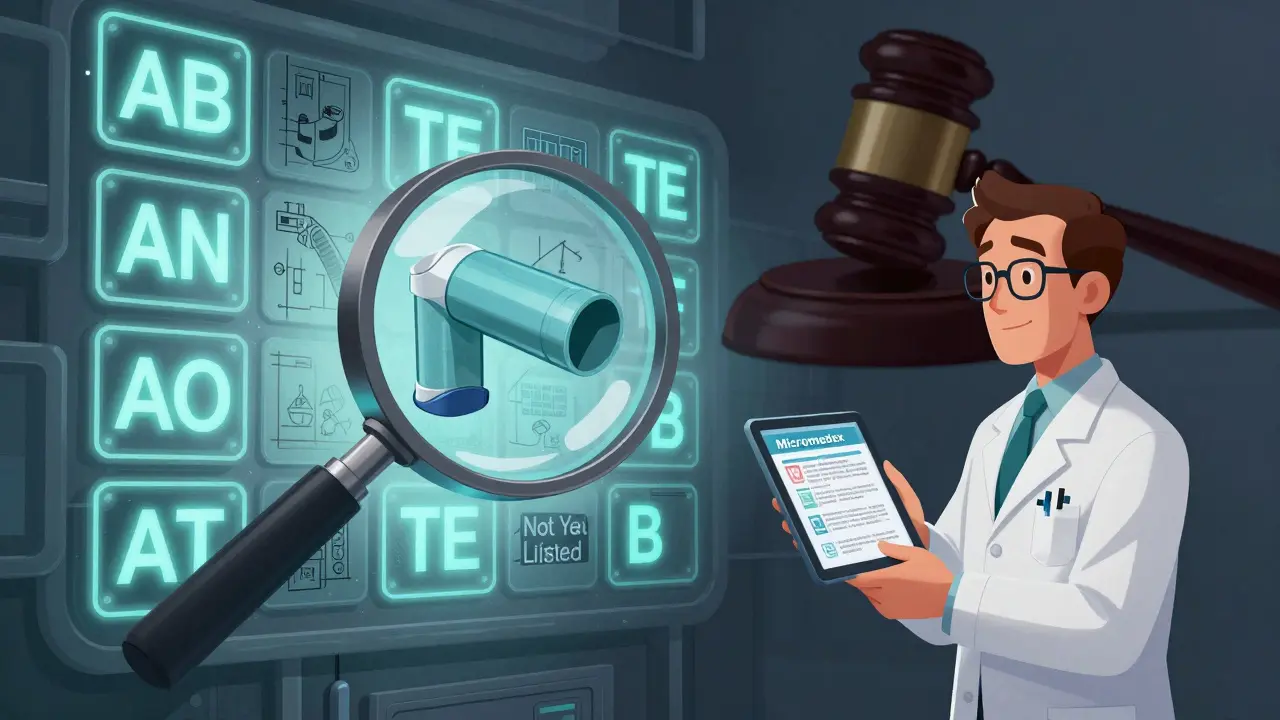

The second letter adds detail. Most generics you’ll see are rated AB. That means they’ve passed both pharmaceutical and bioequivalence tests using human studies. Other codes like AN (nasal aerosols), AO (oral solutions), and AT (topicals) tell you the product type and how equivalence was tested. As of April 2024, the Orange Book lists 16,500 drug products. Of those, 15,900 - or 98.7% - are rated AB.

Pharmacists don’t flip through paper books anymore. Over 72% use the free FDA Orange Book mobile app, downloaded more than 450,000 times. Others pull data directly from pharmacy systems like PioneerRx or QS/1. The whole check takes 8 to 12 seconds per prescription. But it’s not automatic. The pharmacist must confirm:

- The reference listed drug (RLD) matches the brand prescribed.

- The generic has the same active ingredient and strength.

- The TE code is ‘A’ (or ‘AB’).

- The prescriber didn’t write ‘Dispense as Written’ or ‘Do Not Substitute’.

What Happens When a Drug Isn’t in the Orange Book?

About 5.7% of generic substitutions involve drugs not yet listed. This happens with newer products, complex formulations like inhalers or topical creams, or when the manufacturer hasn’t submitted data. In those cases, pharmacists don’t wing it. They follow the FDA’s Non-Orange Book Listed Drugs framework.They cross-check with drug databases like Micromedex or Lexicomp. They review FDA product-specific guidances. They look at the manufacturer’s ANDA submission summary. But here’s the catch: if they substitute without using the Orange Book, they’re legally exposed. In the 2019 Texas case State Board of Pharmacy v. Smith, a pharmacist was disciplined for substituting a non-Orange Book-listed generic. The court ruled: ‘The Orange Book is the law. Deviating from it is negligence.’

Why Not Just Use Any Drug Database?

Many pharmacies use commercial databases like First Databank or Micromedex. They’re fast, user-friendly, and often integrated into dispensing systems. But they’re not the law. A 2021 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that 99.3% of pharmacists rely on the Orange Book as their primary source. Only 62.7% use commercial tools as backups.Why? Because the Orange Book is the only source that carries legal weight. If a patient has an adverse reaction after a substitution, the pharmacist’s defense isn’t ‘I checked Micromedex.’ It’s ‘I checked the Orange Book.’ That’s the difference between being protected - and being sued.

Complex Drugs and the Future of Equivalence

Not all drugs are created equal. Inhalers, topical creams, and injectables are harder to replicate. Their effectiveness depends on how the drug is delivered - not just how much gets into the blood. Traditional bioequivalence tests (Cmax, AUC) don’t always capture that.Dr. Randall Stafford from Stanford pointed this out in a 2021 JAMA Internal Medicine commentary. The FDA agrees. That’s why they’ve created product-specific guidances for 1,850 complex drugs - including corticosteroid creams, nasal sprays, and inhalers. These guidances define new testing standards, like in vitro dissolution profiles or lung deposition studies.

But here’s the reality: even for these complex products, the Orange Book still rules. As of June 2024, only 47 of 350 approved biosimilars (the biologic version of generics) are listed in the Purple Book - the biologics equivalent of the Orange Book. Pharmacists are left navigating a gray zone. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists says the system still works: ‘Substitution error rates are only 0.03% when properly implemented.’

Training, Compliance, and the Bottom Line

Pharmacies don’t just hand new hires a manual. They train them. The National Community Pharmacists Association reports 92.4% of pharmacies require 2-4 hours of formal Orange Book training during onboarding. Competency tests show 89.3% accuracy after training.Why? Because the stakes are high. In 2023, 8.9 billion prescriptions were filled in the U.S. - 90.7% were generics. That’s a $621 billion market. The Orange Book system saves patients and insurers $12.7 billion a year by enabling safe substitution. But it only works if every pharmacist follows the same rules.

The FDA’s 2023 Strategic Plan for Generic Drugs commits $28.5 million to improve equivalence testing for complex drugs. GDUFA III, implemented in 2023, added stricter review standards. And the agency is working to integrate the Orange Book directly into electronic health records - so pharmacists get real-time alerts during dispensing.

Final Check: What You Should Know

You don’t need to memorize TE codes. But you should know this:- Generic drugs are not ‘cheaper versions’ - they’re legally required to be the same.

- Pharmacists don’t make substitution decisions lightly. They follow a federal standard.

- If your prescription says ‘Dispense as Written,’ the pharmacist can’t switch it - even if the generic is rated AB.

- If you notice a change in how a generic works, tell your pharmacist. It’s rare, but not impossible.

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s the most rigorously tested, legally enforced, and scientifically sound drug substitution system in the world. And it works - every day, for millions of people.

Can a pharmacist substitute a generic without my permission?

In 49 U.S. states, yes - if the prescription doesn’t say ‘Dispense as Written’ and the generic is rated ‘A’ in the FDA Orange Book. The pharmacist must still follow state law and check for any restrictions. If you don’t want a substitution, you can always ask for the brand name or request ‘Dispense as Written’ on the prescription.

Are all generics rated ‘AB’ in the Orange Book?

No. About 98.7% of rated products are AB, meaning they’ve passed both pharmaceutical and bioequivalence tests. The rest may be rated ‘A’ with other second letters (like AN or AT) for special delivery systems, or ‘B’ if they haven’t met equivalence standards. Always check the full TE code - not just the ‘A’ - for accuracy.

Why do some generics cost more than others?

Price differences don’t reflect quality or equivalence. Two AB-rated generics for the same drug can cost differently due to manufacturing scale, distribution networks, or market competition. The Orange Book doesn’t track price - only therapeutic equivalence. A higher price doesn’t mean it’s better. It just means someone’s paying more.

What if the Orange Book says ‘A’ but I feel different on the generic?

You’re not imagining it. While rare, some patients report differences - especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs like thyroid meds or seizure medications. The science says these drugs are equivalent, but individual biology can vary. Tell your pharmacist and doctor. They can switch you back or try a different generic manufacturer. The Orange Book doesn’t override patient experience - it just sets the legal baseline.

Do biosimilars use the Orange Book?

No. Biosimilars - which are complex biological drugs, not chemical generics - are listed in the FDA’s Purple Book. As of June 2024, only 47 of 350 approved biosimilars are listed there. Pharmacists must use the Purple Book for these, and substitution rules are less standardized than for traditional generics. Many states still require prescriber approval for biosimilar substitution.