Immunosuppressant Drug Level Checker

Check Your Tacrolimus Levels

Tacrolimus levels must stay between 5-8 ng/mL to prevent rejection or toxicity. This tool helps you interpret your lab results.

Why Immunosuppressants Are Non-Negotiable After Transplant

Your new organ is a gift-but your body doesn’t see it that way. To your immune system, it’s an invader. Without drugs to quiet that response, rejection happens fast. In the 1960s, kidney transplant patients had a 50% chance of surviving one year. Today, thanks to immunosuppressants, over 90% do. But these drugs don’t just block rejection-they change your life in ways most people never expect.

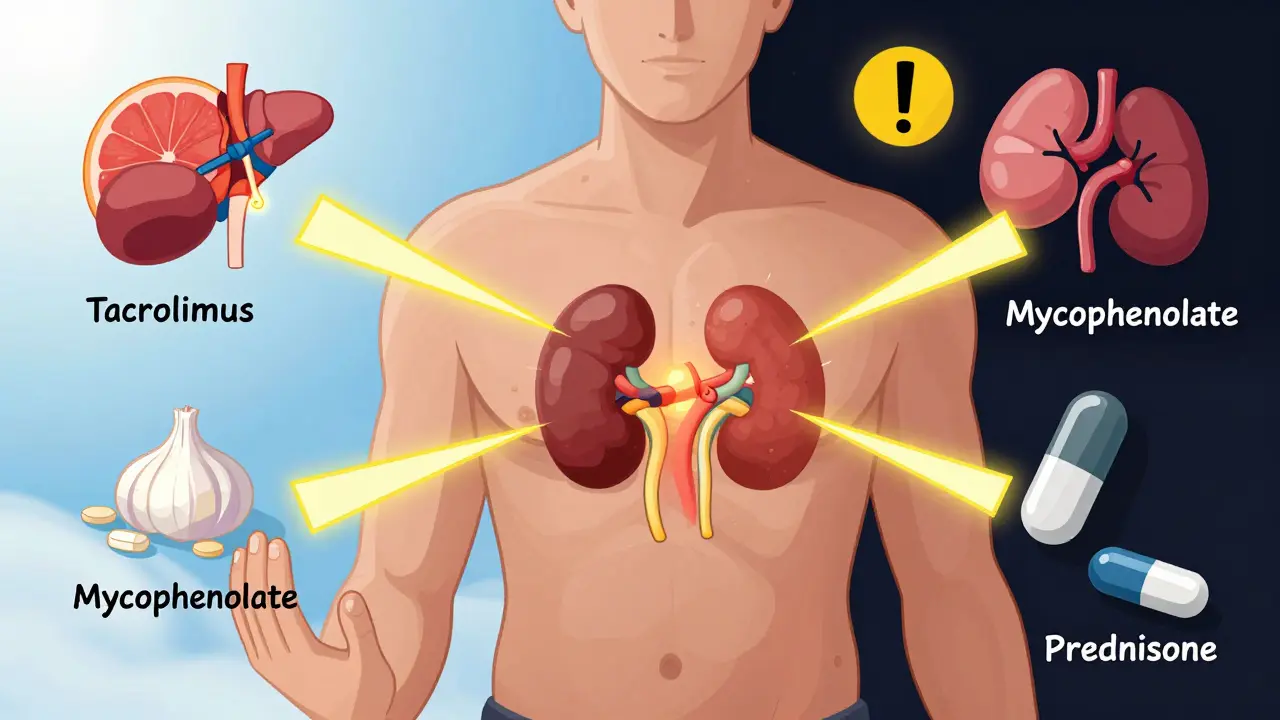

Almost every transplant recipient in the U.S. takes a combo of three drugs: a calcineurin inhibitor (usually tacrolimus), an antimetabolite (like mycophenolate), and a steroid (prednisone). Tacrolimus is the most common, used in 92% of kidney transplants. It works by stopping T-cells from attacking the new organ. But it’s not gentle. It has a razor-thin window between working and causing harm. Too little? Rejection. Too much? Kidney damage, tremors, or diabetes.

How These Drugs Talk (and Fight) With Everything Else You Take

Immunosuppressants don’t live in a vacuum. They’re processed by the same liver enzymes that handle hundreds of other drugs-especially CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein. That means even harmless over-the-counter meds can turn dangerous.

Take fluconazole, a common antifungal for yeast infections. It can boost tacrolimus levels by up to 200%. One patient in Boston reported feeling dizzy and nauseated after starting it for a rash. Her tacrolimus level jumped from 7 ng/mL to 18 ng/mL-well above the safe range. She ended up in the ER. On the flip side, rifampin (used for TB or staph infections) can slash tacrolimus levels by 90%. That’s a rejection waiting to happen.

Even grapefruit juice is a red flag. It blocks the enzyme that breaks down tacrolimus and cyclosporine. One glass can spike levels for days. Herbal supplements? Even riskier. St. John’s wort, garlic pills, echinacea-they all interfere. A 2020 study found nearly 40% of transplant patients were taking at least one supplement that clashed with their meds. No one asked them. They didn’t think it mattered.

The Most Common Side Effects-And How They Really Feel

Side effects aren’t just listed in brochures. They’re daily realities.

- Diabetes after transplant (NODAT): One in five kidney recipients develop it. Tacrolimus is the main culprit. It messes with insulin release. Many don’t know they’re at risk until they’re diagnosed with high blood sugar during a routine checkup.

- Weight gain and "moon face": Prednisone causes fat to redistribute. People report gaining 15-20 pounds in six months. Faces swell. Backs develop a "buffalo hump." Some avoid mirrors. One heart transplant patient said, "I didn’t recognize myself. I felt like a stranger in my own skin."

- Shaking hands and tremors: Common with tacrolimus. A man in Cleveland said he couldn’t button his shirt or hold a coffee cup without spilling. He thought it was aging-until his doctor checked his drug level.

- GI chaos: Mycophenolate causes diarrhea in 32% of users, nausea in 28%. One Reddit user described it as "constant stomach cramps and urgency-you can’t leave the house without planning a bathroom route."

- Infections: With your immune system turned down, even a cold can turn into pneumonia. Listeria from deli meats? Deadly. Raw oysters? A no-go. A 2022 survey found 85% of recipients have had at least one serious infection since transplant.

What Happens When You Stop Taking Your Meds

It’s not just about forgetting a pill. It’s about thinking, "I feel fine, why do I need this?"

Non-adherence causes 22% of late graft losses. That’s one in five people who lose their transplant because they stopped taking their drugs. Some skip doses because of cost. Others because of side effects. One woman in Texas stopped her tacrolimus after three years because she couldn’t handle the tremors. She lost her kidney within six months.

Transplant centers track adherence closely. Many use electronic pill dispensers that alert patients and send data to the clinic. One study showed adherence jumped from 72% to 89% when patients used them. But tech doesn’t fix fear. If you’re scared of side effects, you need to talk to your team-not stop.

Alternatives and New Hope on the Horizon

Not everyone has to stay on the same drugs forever.

Some patients switch from tacrolimus to sirolimus (Rapamune) because their kidneys are failing from drug toxicity. Sirolimus is gentler on the kidneys-studies show slower decline in kidney function over five years. But it brings new problems: mouth sores, high cholesterol, and slower wound healing. One liver transplant patient switched and saw his kidney function improve from GFR 38 to 52-but now he’s on a statin and gets mouth ulcers every winter.

There’s also belatacept (Nulojix), a newer drug that doesn’t harm the kidneys like calcineurin inhibitors. It cuts heart disease and cancer risk. But it causes more early rejection. It’s only for certain patients, usually those with low immune risk.

And then there’s the future. The ONE Study found that 15% of kidney transplant recipients achieved "operational tolerance"-meaning their bodies accepted the organ without any drugs. They stopped immunosuppressants and stayed healthy for two years. It’s rare. But it’s proof that tolerance is possible. Researchers are now testing regulatory T-cell therapy to make this happen for more people.

How to Stay Safe-And Keep Your Transplant

Living with immunosuppressants means being your own best advocate.

- Know your drug levels. Tacrolimus should be 5-8 ng/mL in the first year. If you’re above 10, you’re at risk. Below 5, you’re at risk of rejection.

- Get blood tests every month-CBC, kidney function, glucose, lipids. Don’t skip them.

- Never start a new medication, supplement, or herb without telling your transplant team-even if it’s "natural."

- Avoid raw or undercooked foods. No sushi, rare steak, or unpasteurized cheese. Listeria doesn’t care if you’re healthy otherwise.

- Wear a mask in crowded places, especially flu season. Wash hands constantly.

- Report fever over 100.4°F immediately. It’s not "just a cold."

- Ask about steroid withdrawal. Many centers now stop prednisone after 7-14 days for low-risk patients. It cuts weight gain, diabetes, and bone loss by 35-40%.

The Emotional Toll Nobody Talks About

It’s not just physical. It’s psychological.

"Steroid rage" is real. One man said he yelled at his wife over spilled coffee and didn’t remember it the next day. Another woman cried for no reason every afternoon. Depression and anxiety are common-partly from the drugs, partly from the constant fear of rejection.

And the isolation. You can’t go to concerts, crowded malls, or family gatherings without thinking, "Will this make me sick?" One patient on Reddit said, "I’m alive, but I’m not living. I’m just surviving."

But there’s also hope. The same Reddit community is full of people sharing tips: "I started yoga and sleep better." "I found a dietitian who helped me lose the steroid weight." "My support group saved me."

Final Reality Check

You’re not alone. Over 186,000 Americans live with a functioning transplant. Nearly all of them take immunosuppressants. The drugs are harsh. The side effects are real. The risk of rejection never goes away.

But here’s the truth: without them, you wouldn’t be here. The trade-off isn’t fair. But it’s the best option we have-for now. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s balance. Managing side effects while keeping your organ alive.

Ask questions. Keep your team updated. Don’t hide symptoms. Your transplant isn’t just a surgery-it’s a lifelong partnership with your body, your meds, and your care team.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Feeling fine doesn’t mean your immune system has stopped trying to reject the organ. Stopping immunosuppressants-even for a few days-can trigger acute rejection, which often leads to organ failure. Most transplant recipients must take these drugs for life. Only rare cases, like those in clinical trials for immune tolerance, have safely stopped them.

Why is tacrolimus preferred over cyclosporine?

Tacrolimus is more effective at preventing rejection. In the 2005 ELITE-Symphony trial, one-year graft survival was 83.1% with tacrolimus versus 76.6% with cyclosporine. It also has lower rates of high blood pressure and gum overgrowth. But it carries a higher risk of new-onset diabetes and tremors. Still, because of its superior results, 92% of U.S. kidney transplant centers use it as first-line therapy.

Do immunosuppressants cause cancer?

Yes. Long-term immunosuppression increases cancer risk by weakening immune surveillance. Skin cancers (especially squamous cell carcinoma) are the most common, affecting about 23% of liver transplant recipients. Overall, transplant patients have a 2-4 times higher risk of cancer than the general population. Regular skin checks and avoiding sun exposure are critical. Some drugs, like sirolimus, may actually lower cancer risk compared to calcineurin inhibitors.

Can I take vitamins or supplements with my transplant meds?

Only under direct supervision from your transplant team. Many supplements interfere with immunosuppressants. St. John’s wort, garlic, echinacea, and even high-dose vitamin E can reduce drug levels and trigger rejection. Some can also increase toxicity. Always check with your pharmacist or doctor before starting anything new-even fish oil or a multivitamin.

How often do I need blood tests after a transplant?

In the first few months, you’ll need blood tests twice a week to monitor drug levels (like tacrolimus). After three months, it’s usually weekly, then biweekly, and eventually monthly. You’ll also need monthly complete blood counts (to check for low white cells), quarterly lipid panels (for cholesterol), and biannual glucose tests (for diabetes). Skipping tests puts your transplant at risk.

What should I do if I miss a dose of my immunosuppressant?

If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember-unless it’s close to your next scheduled dose. Never double up. If you miss more than one dose, contact your transplant team immediately. Missing doses increases rejection risk. Many centers now use electronic pill dispensers that alert you and notify your clinic if you skip a dose.

Are there cheaper alternatives to brand-name immunosuppressants?

Yes. Generic versions of cyclosporine (Gengraf) and mycophenolate (Myfortic) are available and cost 25-30% less than brand names. Tacrolimus generics are expected to become available after its patent expires in 2025. Always confirm with your pharmacist that the generic is bioequivalent and approved for transplant patients. Some insurance plans require prior authorization for generics.

Can diet affect how immunosuppressants work?

Yes. Grapefruit and Seville oranges block the enzymes that break down tacrolimus and cyclosporine, causing dangerous spikes in drug levels. High-fat meals can delay absorption. Consistency matters-eat similar meals at the same times each day. Your transplant team may refer you to a dietitian who specializes in post-transplant nutrition to help you manage side effects like high cholesterol, diabetes, and weight gain.

What’s the long-term outlook for transplant recipients on immunosuppressants?

Ten-year survival for kidney transplant recipients is about 65%, compared to 85% for healthy peers of the same age. This gap is mostly due to side effects from long-term immunosuppression-heart disease, cancer, infections, and kidney damage from the drugs themselves. But outcomes are improving. Newer drugs like belatacept and steroid-sparing protocols are helping. The goal now is not just survival, but quality survival-keeping you alive and well for decades.

Is there hope for a future without lifelong immunosuppressants?

Yes. Researchers are working on immune tolerance-teaching the body to accept the organ without drugs. Early trials show promise: 15% of kidney transplant recipients in the ONE Study stopped all immunosuppressants and remained rejection-free for two years. Techniques like regulatory T-cell therapy and mixed chimerism are being tested. While not ready for widespread use, these advances suggest a future where transplant recipients won’t need daily pills.

Managing immunosuppressants isn’t about perfection. It’s about awareness, consistency, and communication. You’re not just surviving-you’re living with a second chance. Make sure your team knows how you’re really doing.

Joy F

January 5, 2026 AT 02:01Angela Fisher

January 5, 2026 AT 18:09Neela Sharma

January 6, 2026 AT 13:45Wren Hamley

January 6, 2026 AT 23:25veronica guillen giles

January 8, 2026 AT 14:55Angela Goree

January 8, 2026 AT 22:09Haley Parizo

January 9, 2026 AT 23:29Shruti Badhwar

January 10, 2026 AT 20:56Liam Tanner

January 11, 2026 AT 19:57Hank Pannell

January 13, 2026 AT 10:21Ian Ring

January 15, 2026 AT 09:43